Beth Immanuel is a friendly and welcoming community. Click here to learn what to expect when you visit.

The Four Mitzvot of Purim

And Mordecai recorded these things and sent letters to all the Jews who were in all the provinces of King Ahasuerus, both near and far, obliging them to keep the fourteenth day of the month Adar and also the fifteenth day of the same, year by year, as the days on which the Jews got relief from their enemies, and as the month that had been turned for them from sorrow into gladness and from mourning into a holiday; that they should make them days of feasting and gladness, days for sending gifts of food to one another and gifts to the poor. So the Jews accepted what they had started to do, and what Mordecai had written to them. For Haman the Agagite, the son of Hammedatha, the enemy of all the Jews, had plotted against the Jews to destroy them, and had cast Pur (that is, cast lots), to crush and to destroy them. (Esther 9:20-24)

The holiday of Purim and its customs come from the book of Esther, especially from the passage above. Mordecai enacted obligations that Jewish people are to follow year after year and observe to this day. Today we might not think twice about this because we open our Bible and find the book of Esther, so these observances seem like all the other biblical commands. However, Mordecai was not Moses. There was no burning bush or Mount Sinai that granted Mordecai authority to make new commandments. At the time that these events happened, there was no book of Esther. On what basis was Mordecai able to institute new obligations for the Jewish people? How is it that the people at that time and all generations of Jews since have accepted the rules that Mordecai made up as commandments from God?

In the Torah, there is a certain type of sacrifice called the sacrifice of thanksgiving, or korban todah. After the priests slaughtered this animal and applied its blood and sacred portions to the altar, the meat was roasted. The one offering it had to serve and eat it along with copious amounts of bread on the same day that the animal was offered. To do this, he had to enlist help from numerous friends.

A person was required to bring such an offering any time he was saved from danger, such as if he was sick and then healed, if he survived a sea or desert journey, or if he was released from captivity. See Psalm 107 for examples of this.

The point of the korban todah is to give thanks. Because it must be eaten by so many people so quickly, it will grant an opportunity for everyone to learn of the great salvation that occurred for this person. As the Psalms say,

I will offer to you the sacrifice of thanksgiving and call on the name of the LORD. I will pay my vows to the LORD in the presence of all his people. (Psalm 116:17–18)

There is a biblical obligation for an individual who experiences salvation to thank God publicly. How much more so then for when the entire nation is delivered from danger!

The ordinances that Mordecai enacted were for this very purpose: publicizing the miracle. This is often referred to in Aramaic as pirsumei nisa. Each of the mitzvot of Purim is designed to accomplish this in its own way.

Note for Messianic Gentiles:

It is important for us to note that when Mordecai enacted these laws, he had no intention of imposing them on all people from all nations. Thus, Gentiles do not have a relationship of obligation with these observances. However, all nations clearly benefit from the salvation of the Jewish people. If you are a Messianic Gentile, it is appropriate for you to participate in these practices to whatever extent you can.

Just note that in the remainder of this document, I will be referring to obligation as it applies to Jewish people. This will provide a frame of reference for you to help you understand what participation means.

With that said, let’s begin our analysis of the mitzvot of Purim.

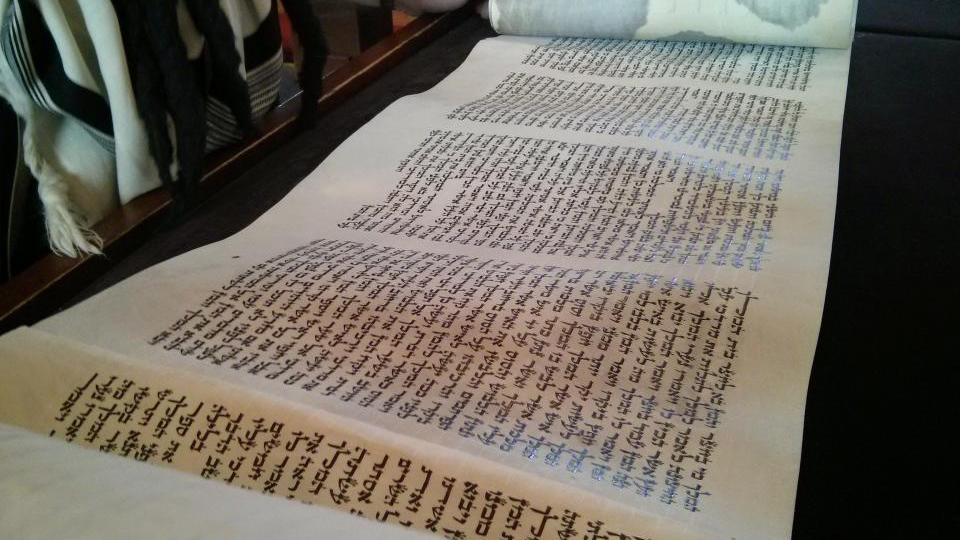

Reading the Scroll of Esther (Mikra Megillah)

Considering that our goal is to publicize the miracle, it stands to logical reason that we should read the story. In fact, that is exactly why Mordecai recorded it in the form of an epistle and why it is in our Bible today.

According to Jewish law:

- The requirement is to read the megillah twice: once at night, and once again in the daytime.

- The requirement applies to both men and women.

- Ideally it is done congregationally, in a synagogue, for both readings. If no other option is available it can be done at home.

- One may listen to another person read it, but they must hear every word that is read.

- Even then, it is best if one follows along with their own parchment (or a printed book if necessary)

The Festive Purim Meal (S’udat Purim)

As the book of Esther indicates, Purim is to be a time of feasting. In fact, this goes well with the theme of the story, which opens with a lavish banquet, and later we find the Jews fasting in supplication for their own lives. How fitting that now that our side wins, we are the ones feasting.

Here are the rules for the Purim feast:

- It must be done in the daytime. If you have a fancy dinner or party on the night of Purim, that is great, but it does not count toward the mitzvah of the Purim feast.

- The normal time for this is in the afternoon, after the minchah prayers. Often it continues on into the night, but the main eating happens in the daytime.

- Meat and wine are normally served at this meal as an expression of joy.

The sages say that what Yom Kippurim accomplishes by fasting, Purim accomplishes by enjoyment.

Purim is not a Shabbat or festival with work restrictions, so you can buy stuff and cook and drive however you like. This is your chance to invite people over to your house, especially people who can’t normally come because of Shabbat!

If you feel that you are too poor to have a Purim meal, then there is good news if you live in a Torah-keeping community. The next two mitzvot will help greatly.

Sending Gifts of Food

The text says Purim is a time for “sending gifts of food to one another” (umishloach manot ish lere’ehu, וּמִשְׁלוֹחַ מָנוֹת אִישׁ לְרֵעֵהוּ). Literally this means “sending food-portions a man to his fellow.”

Since it says “a man to his fellow” or “one to another” in a singular form, the sages say that the obligation is for each person to send a gift to at minimum one other person. If you wish to send a gift to more people, then all the better.

However, the word for “gifts of food” or “food portions” is manot, which is plural. Portions means at least two. That means that the one gift should contain at least two different kinds of food. Or as many different kinds as you want to add.

One more thing to note in our literal reading: it does not say “giving gifts of food.” It says “sending.” Mishloach, sending, implies that you have a messenger, a shaliach. So if you possibly can, it is better to give this gift through a messenger. Just give your present to someone else and say “Please give this to so-and-so for me.” And you can return the favor for them. If you can’t find a messenger, it is OK to give it directly.

This gift of food is not charity. It’s a present, a bit like giving chocolates to your sweetheart. As such, this should not be done anonymously. The purpose is to stir up warm feelings between people, but if you do it anonymously, no one will know who to feel warm feelings for.

To do this, get a container such as a gift bag, a paper plate, a wicker basket, a box, or whatever you like. You can decorate it if you want, but you don’t have to. Put some ready-to-eat food items in there. They should not be things that require any preparation, but you should be able to just open the package and eat or drink. Cookies, roasted nuts, fruit, candy, beef jerky, or a bottle of wine are good examples. It’s always nice to get treats that you wouldn’t normally get for yourself.

When choosing recipients, think of people who you would like to be better friends with. People who mean a lot to you but don’t get a lot of attention.

Now if you receive the portions of food, you are free to do with them what you want. One thing you can do is serve them at your festive Purim meal! Convenient!

Giving Money to the Poor

The last item and perhaps the most important on the list is gifts for the poor. This is not the same thing as sending portions of food to one another. This is separate. In this case, we’re talking about giving actual cash money to actual poor people. In the other case, we’re talking about giving treats to friends, regardless of their wealth. Big difference.

Now there’s an obvious question. We give money to the poor every day. It is always a mitzvah to give to the poor. What is different on Purim?

This gift is for the purpose of publicizing the miracle. So, if the poor person does not know about the Purim story or learn about it, then does not serve its purpose. That means that just dropping coins into a tzedakah box or donating to a relief organization does not fulfill this mitzvah, even though it is still a good deed.

Like the other mitzvot, the gift to the poor must be given during the daytime on the day of Purim. And it must be given early enough in the day that theoretically, the poor person could use that money on Purim for the festivities that will take place later, if they want to. That means that this money should be given and received immediately after the morning service and Megillah reading.

If you recall the portions of food only is to one person because it says fellow, singular. In this case, the Hebrew word for “poor,” (evyonim) is plural, meaning that each person should give something to at least two poor people.

There is not required amount of money to give. However, as a rule of thumb, one would do well to give as much money to the poor as they spend on the other mitzvot. If you are a wealthier person and go all out and spend $1000 on a lavish Purim banquet for yourself and $500 on treats for your friends, then consider also giving another $1500 to the poor. Perhaps a good approach would be to set your complete budget first, then divide it in half and designate one half for this purpose. However, if you are poor, it may be better to fulfill the mitzvah with a minimal amount, such as a quarter for each recipient.

This gift can be given anonymously if you desire. There is typically someone in the synagogue who can collect the funds and then distribute them to needy people.

The money given for this purpose on Purim does not count toward tithes. It is its own separate budget item.

If you are in a Torah-keeping community and are too poor afford a Purim meal, then let someone know you’re poor. On Purim, the policy is not to be picky about who we consider poor, but we “give to one who asks.” If you are poor enough to be humble enough and ask, then you are poor enough to receive.

Bonus: The Fast of Esther and the Half Shekel

Now, you might be thinking, isn’t there something about half-dollar coins? That is something different, and it does not take place on Purim itself, but on the day of the fast of Esther.

The fast of Esther is a time to prepare for spiritual battle. It reflects the fast that Esther and all the Jews undertook before she went in before the king.

This is a minor fast, so it’s only for people in good health. It’s a fast from all food and drink from early dawn until dark.

Normally this takes place on the day leading up to Purim and you break the fast after the reading of the megillah. However, when Purim begins on Saturday night, the fast is moved to the previous Thursday.

Just before minchah, the afternoon prayers, on the day of the fast, we contribute three coins for each member of our family. This commemorates the half-shekel given for the construction of the tabernacle. The custom is to use coins in half the basic denomination of the current locale, so for us we use half dollars.

This donation is also for the poor only. It cannot go toward synagogue upkeep and the like. However, it is not for publicizing the miracle so it can go to a cause like Acts for Messiah or some other relief fund, or to any poor people you know.